Very soon we will not be reading about gardens and Roman sites but walking among them! So, let me get to the final set of gardens: Great Dixter, and Kew, which are also the final two venues we will visit.

In the mid to late 20th century, Great Dixter was developed by gardener and prolific garden writer Christopher Lloyd into an internationally known site for propagation and planting techniques, for garden students, trainees, and volunteers. The gardens follow in the Arts and Crafts tradition introduced in the notes for Hidcote and Sissinghurst. In fact, architect Edwin Lutyens who worked with Gertrude Jekyll assisted Nathaniel Lloyd, Christopher’s father, in the design of the house and the initial layout of the garden. Histories frequently draw attention to Lutyens’ use of curved steps of natural material.

There is a 20-minute video, “Stunning Great Dixter Garden: Five Fabulous Arts and Crafts Features,” with rather jazzy music but stunning photography that I recommend—with audio turned low.

Other features that Great Dixter is know for are the herbaceous boarders, which Lloyd said are more properly called “mixed boarders,” flower meadows, topiaries, and rooms defined by yew hedges cut in an inverted keystone shape, wider at the bottom than the top to allow sun to reach the entire shrub, keeping both top and bottom green and lush. Notice the long boarder below juxtaposed to the flower meadow-like lawn. It might not surprise you that the Lloyds were influenced by William Robinson’s The Wild Garden also mentioned in the previous set of notes. In the second photo below, the peacock garden, topiary peacocks (identified as squirrels by some) can be seen above inverted keystone bases.

One final photo will illustrate the bold lushness and experimentation with color and plant type and foliage Great Dixter is known for.

Our final garden visit will be Kew, maybe the most widely known English garden and reportedly the largest botanic collection in the world. Actually, Kew started as a private botanic collection by Princess Augusta, the mother of George III in 1759. The 18th century was the great period of world-wide plant collection and the founding of botanic gardens—either new or transformed physic gardens of earlier periods. In 1840, Kew became the property of the government as opposed to the Crown and was opened to the public.

For an alluring taste of Kew, or more properly the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, I’ll point out three essential buildings: the Palm House, the Temperate House, and the Great Pagoda. First the Palm House: global plant collection inevitably necessitated a way to maintain plants unsuited to local climates. The answer was glass houses, or what we might call greenhouses today. For Kew, the glass house served both botanical and nationalistic purpose. A Victorian show-piece, the first glass house to be built on such a large scale at the time, and the first large scale structural use of wrought iron, the Palm House opened in 1848.

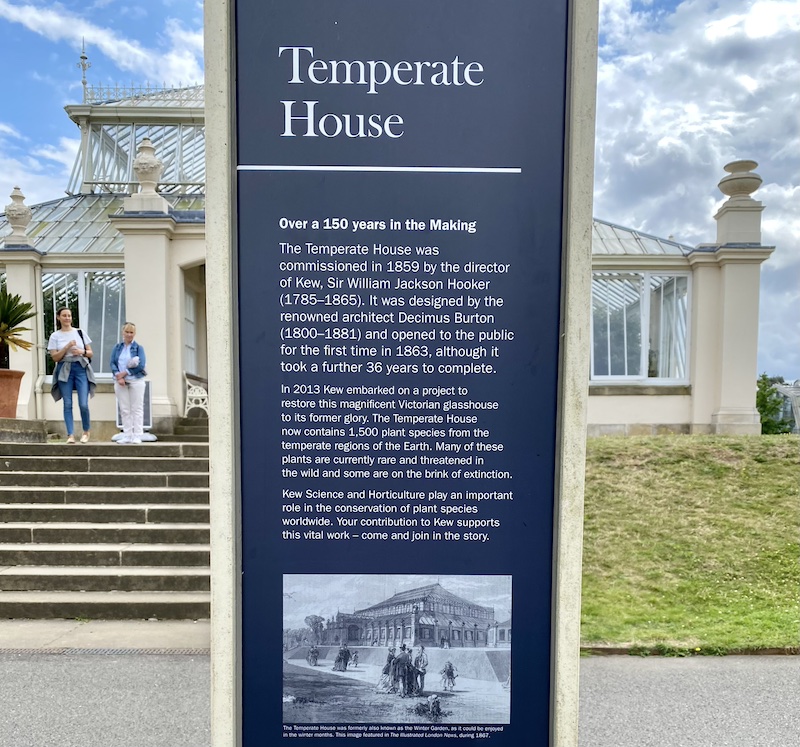

The Palm House was followed by the Temperate House in 1863 (an herbarium came between in 1853). Tender plants from temperate climates can be kept at 50 degrees F throughout the coldest English winters. As the photo below shows, the building is massive. There is a wing on the opposite side of the crossing section as large as the one you see in the image below. The featured photo that opens these notes offers another perspective on the size of the Temperate House.

Both of these botanical gems were preceded by the 10-storey Great Pagoda, built in 1762 as a gift to Princess Augusta. As a result of a major conservation project, it was reopened with its 80 rediscovered and restored dragons in 2018.

Kew is large, 300 acres, with much more to see. I’ve pointed out only three popular sites roughly parallel to Lion, Victoria, and Elizabeth Gates, and Kew Pier, and in a fairly straight line from the Orangery Cafe where we are scheduled to have lunch. For those of you interested in scoping Kew out before we arrive, I recommend the official tourist map available online.

I’ll close out this series of notes now. We can continue our discussions in person very soon.

Thank you Susan. These notes along with their predecessors have whetted my appetite for exploring some wonderful gardens. I am excited and look forward to our trip!

LikeLiked by 1 person