Depending on an on-time arrival in Manchester, our English garden and villa tour will begin appropriately with the Mamucium Roman Fort and Gardens Reconstruction. The key word here, however, is reconstruction. It is a site I am not familiar with, so I’ll simply note that Manucium, now a part of an Urban Historical Park, dates from 79 CE and its iconic north gate was reconstructed in 1984 incorporating stones from the original gate. By all indications, though, it is a good example of a city coming to appreciate its Roman past after considerable destruction in the enthusiasm of the Industrial Revolution. That repository of all information, Wikipedia, provides a good rundown of Mamucium’s history. Chedworth, however, is a site I know well enough to point out some interesting details.

Begun in the early 2nd century CE, Chedworth, one of the largest Roman Villas so far excavated in Britain, was occupied and developed into the 5th century. The first photo below shows the west range of buildings on the left and the north range directly ahead from the perspective of a gateway in the east wall. The second photo shows the north range from the perspective of the end of the western rooms. A detailed diagram of the villa and description of its architectural development can be found on British History Online for anyone interested.

When we visit, the Tudor-like building located in the middle of the three-sided rectangular Roman compound will stand out like an historical anomaly. And it is. It was built subsequent to 1864 excavations to house discovered artifacts and function as a lodge.

Here are a few Roman features to be looking for, though. Chedworth is known for its beautiful mosaics. In particular, look at this floor of the dining room and what is believed to be a depiction of winter in the lower left of the first photo and the lower right of the third one. “Winter” also serves as the featured image for this post. The center image shows a geometric, rug-like design that borders the pictorial designs to its right.

The large cavity in the dining room floor points us to another feature worth noting: heating. Many of the rooms were heated by a hypocaust system circulating hot air/steam between stacked tiles or stones supporting a floor above.

Try to get a look into the opening if you can to get an idea of how the technology worked. Above, hypocaust supports can be seen in the north range, which also houses an immersion bath on the left below and cool plunge baths on the right. (The photo of the plunge bath looks directly down into its depth.)

Back to the mosaics, though. These geometric design floors are in the bath suites in the west range. There are other design and pictorial mosaics to be seen as well.

There is another feature of Chedworth to point out because it is easily overlooked, and that is the nymphaeum or shrine to water nymphs. It is located diagonally just outside the west and northern ranges. The remains of the original porticoed shrine, an octagonal pool backed by a curved wall of Roman brickwork, it is still fed by a fresh water spring. That spring was likely a key resource in determining Chedworth’s location.

Before I mention the final photos I’ll post for Chedworth, it seems like a good time to note that my photos are not recent ones, and subsequent discoveries, cleanings, and protective structures have certainly appeared in the past few years. Here are the last Chedworth images, though. These 2 inch snails are the largest I had ever seen. After my visit to the villa, I learned that they are Helix Pomatia, the escargot or Roman snails, purposely introduced to Chedworth as a Romano-British delicacy about the time of its founding. They were there a decade ago. I hope that they will still be there in June.

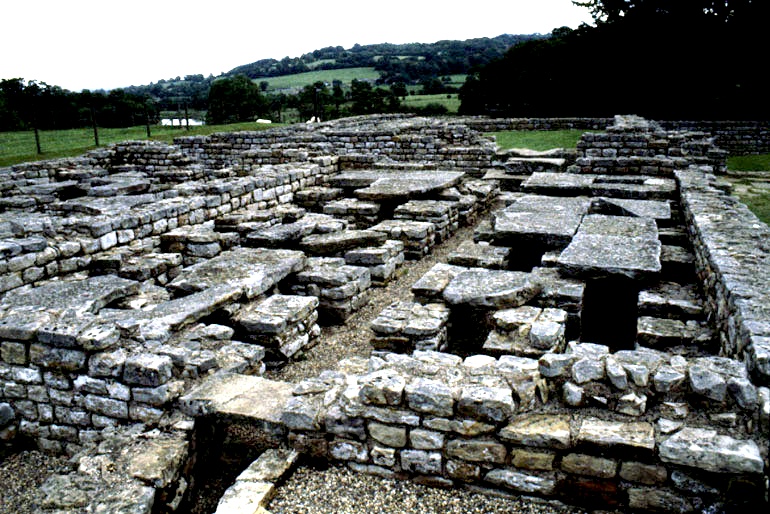

As for Chesters Roman Fort, established about 124 CE, it was one in a series of permanent forts built along Hadrian’s Wall, and it remained in use until the 5th century departure of Rome from Britain. A calvary fort, it housed about 500 troops. What remains to be seen are foundations excavated in the 19th century. The aerial view below is taken from the English Heritage website on the History of Chesters Roman Fort, a worthwhile site to visit.

Prominent in the aerial photo is the fort’s bath complex facing the river North Tyne. On the left below is my old photo showing the complex from the back and a little higher on the hill. The second photo is of the officers’ quarters. Below that are two images of the fort’s foundational walls.

My images of Hadrian’s wall are unfortunately so old that they are on slides! So, I leave you with a lovely photographic capture of sheep near the wall. More importantly, though, I want to alert tour members to an upcoming email with great informational links to Hadrian’s Wall compiled by my Classics colleague and tour co-leader Sam Pezzillo.

Just wonderful. Love old ruins!

LikeLike

Very interesting post. My British gardening friends always complain about snail’s devastating their gardens. Now I see the reason.

LikeLike